things that have to go in

Recently, I went to the New-York Historical Society—don't ask me about that hyphen, I have no idea—to peruse an exhibit of Robert Caro artifacts. Caro, author of The Power Broker and four volumes (so far) of the definitive Lyndon Johnson biography, bequeathed his archives to the museum a couple of years ago.

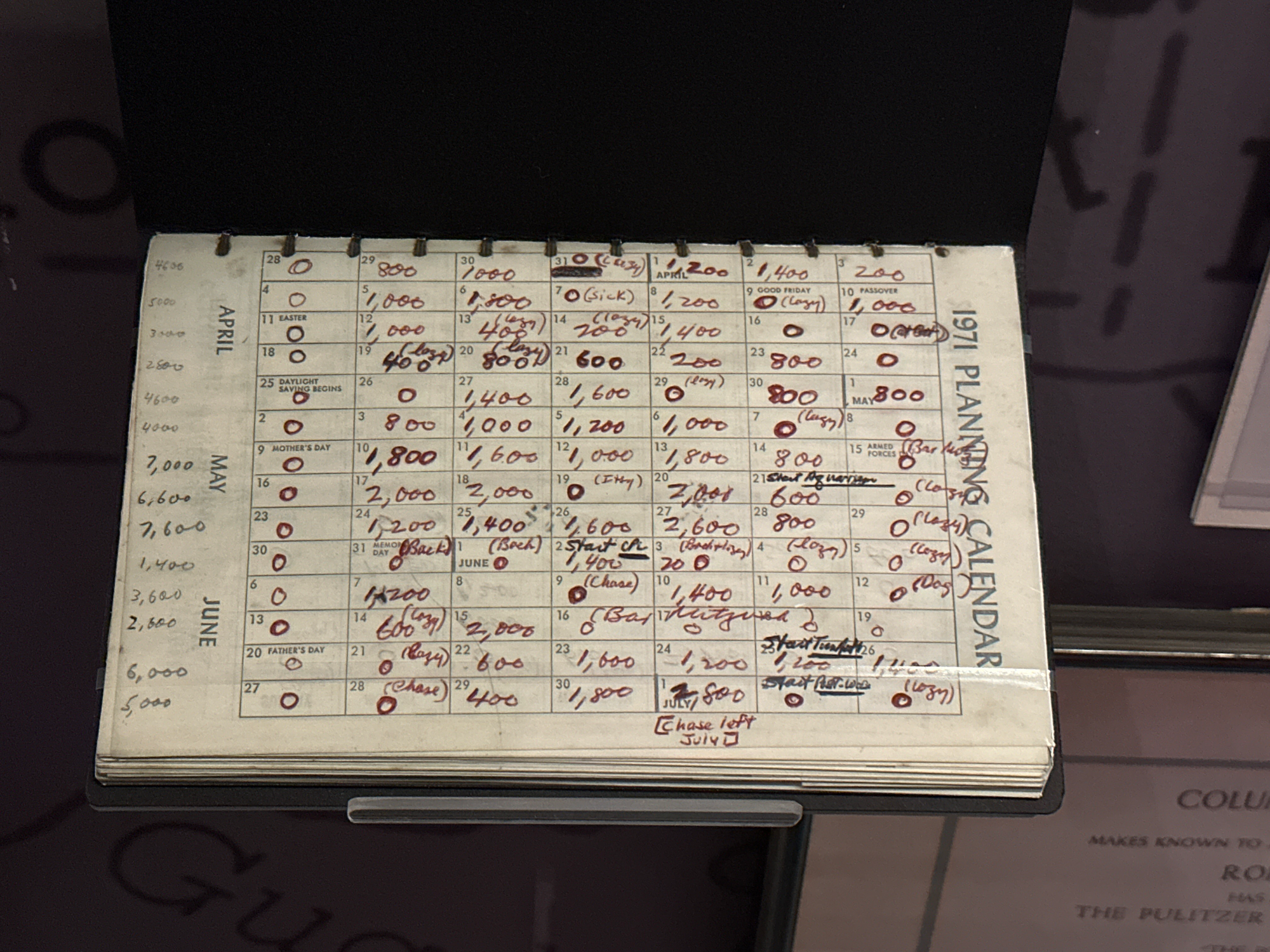

I've belabored the importance of word count goals before (whether or not you have an outside deadline to meet). Caro has never met a book deadline he couldn't miss (by years) but blame his extensive research process. He's definitely been writing:

That photo makes me happy.

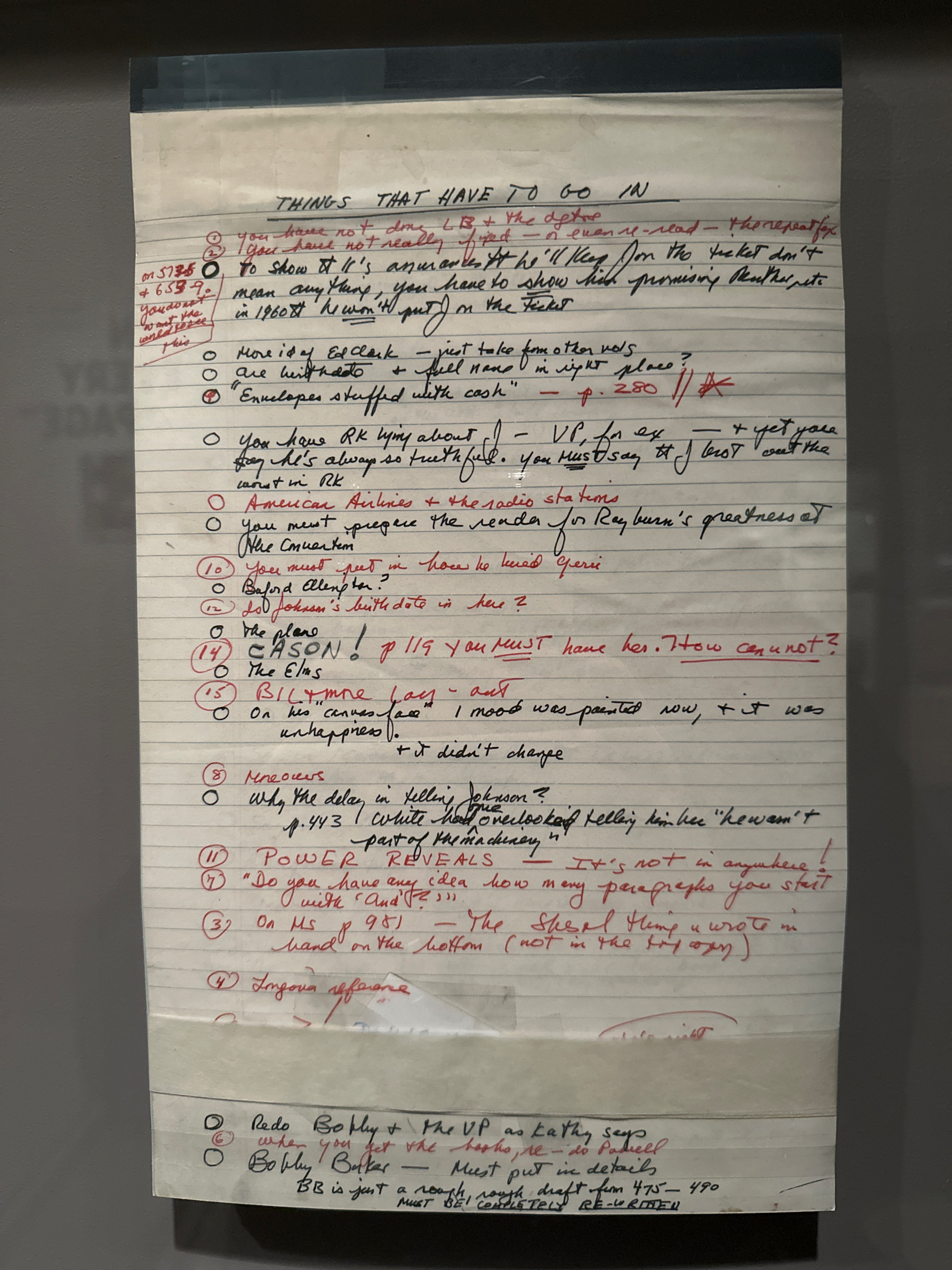

Also striking was another document on display. Previously, I've discussed the usefulness of a punch list: a set of writing tasks kept separate from the manuscript. You get to a point in developing a book where it helps to see all the remaining work in one place, not scattered throughout the document as a series of comments. Collating makes it easier to grasp the scale of the remaining work—and plan accordingly.

As it turns out, Caro keeps punch lists, too:

A top-down view helps with any large document: chapter, book, whatever. Some tasks—"tighten this section by 100 words"—might take only an hour or so. Others will require days of effort: "Explain French Revolution here." When budgeting your remaining time, you must gauge the scale of each task before deciding which one to tackle first. Otherwise, you risk blowing your temporal budget on a slew of minor changes only to realize you've left something crucial (and massive) untouched.

When I tutored for the SAT, kids would get stuck on challenging problems early in the test. Instinctively, they'd keep working on them until they had an answer. This strategy might make sense in high school calculus, but it's deadly on the SAT, where questions aren't arranged in difficulty order. Meanwhile, each correct answer counts equally toward your score. Typically, after sinking a disproportionate amount of time into a handful of complicated questions in the first half, they'd run out of time on the second with many easy questions still unanswered.

Instead, I'd advise them to skip all the hard questions and answer only the ones they know they can solve quickly. Having gotten to the end of the test, they could then go back and address the tougher ones until the clock ran out. (Save your money—this is the only technique that boosts an SAT score. You're welcome.)

Contrariwise, a manuscript punch list ensures that you are addressing the most important and often the most challenging problem. More minor tweaks can always be resolved later if time permits.

p.s. One more SAT tip: On a multiple-choice question, it's always worth guessing. There's no longer a quarter-point penalty. If your kid is stuck, tell them to cross out any answers that can't be right and guess from the remaining options. Now you really owe me.