a 16th-century lesson on finding your niche market

This article first appeared in modified form on the CreativeLive blog.

A piece in the New York Times alerted me to a tribute to the Renaissance printer Aldus Manutius on display at New York City’s posh Grolier Club. I took it upon myself to see the exhibit.

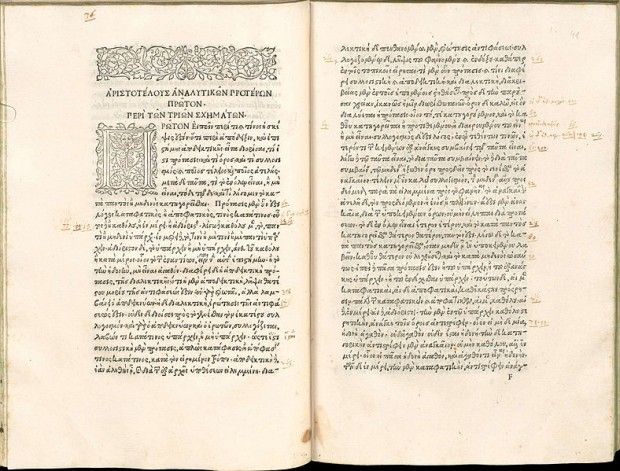

Manutius, a Venetian, blind to other pursuits, was a pivotal figure in the early printing era, responsible for the very first printed editions of many of the great works of Greek literature that survive to this day, from Plato to Herodotus.

He also invented italics.

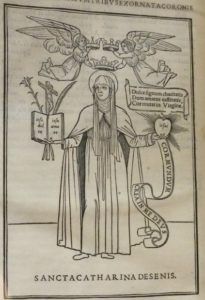

If you look at this woodcut of St. Catherine of Siena, from an edition of the Epistole Devotissime printed in 1500, you’ll notice that she has a book open in her right hand. On the pages of that book are 5 words that represent the debut of italic type, inspired by handwritten cursive writing and designed by Manutius’s typographer, Francesco Griffo. Manutius used italics to squeeze more words on a line, allowing him to create pocket-sized editions that people could carry with them, a sort of Sony Walkman of reading.

Eventually Aldus created an entire Portable Library of classics. Thus, artistic innovation was driven by commercial need. (Are you taking notes?)

Manutius wanted to create a product that filled a hole in the marketplace: affordable editions of great, then-dwindling Greek and Latin works that you could carry everywhere.

Soon, people were reading Sophocles and Horace while waiting in line for Shakespeare in the Park tickets (the difference being Shakespeare was literally in that park) and the op-eds were complaining about how everyone had their noses buried in these newfangled gadgets and that nobody really talked anymore.

Five words were just the beginning; in 1501, Manutius published a collection of the works of Virgil entirely in italics. (Did I mention that he also introduced the semicolon’s use to print?)

What most impresses me about creating an entire book in italics is that Manutius did it entirely without the benefit of ⌘-I. Mind-boggling.

(Note: This would have been Alt-I to users of Windows 0.01, the pre-Renaissance operating system whose lax antivirus security had previously been responsible for the rapid spread of the Black Death, a little-known fact today because Microsoft’s 16th-century PR flacks successfully shifted the blame to rats, another factor in the preference for apples among rats to this day.)

Manutius founded his operation, the Aldine Press, in order to put great books in the hands of everyone. A humanist and an artist, he founded a thriving operation that outlived him, one that was so successful that many imitators copied his logo, his types, even entire books.

Manutius’s attempts to defend his intellectual property, including the italic typeface, built the foundation of much of what we believe about copyright and trademark today.

Why was Manutius successful? By identifying an unexploited niche in the marketplace—great works of literature that remained out of reach to the vast majority of the reading population—and then delivering his work to that niche with quality and a passionate attention to detail. And not just a handful of volumes: He cranked out dozens and dozens of editions over the years.

If you’re an artist who sees your work as more of an avocation than a vocation, try Aldus’s approach and build a stand-out business in the right niche market founded on your own artistic talent and vision. After all, if Aldus hadn’t founded the Aldine Press, the classics as we know them today may never have survived to the present. If you don’t pursue your creative passion, what will future generations never know they’re missing?